What We Can Learn From Investment Manias - Part Three

What We Can Learn From Investment Manias - Part Three

In this the third Instalment of David McEwen’s series on the causes of bad Investment behaviour, we take a closer look at that mother of all market crashes: the 1929 Wall Street Crash

US Stockmarket Bubble, 1929

For the first time, many workers began to have surplus incomes above their daily needs and, to make even more money, started investing their savings in the share market. New technology stocks were very popular with one invention, the radio, being seen as something that would revolutionise communications and business.

Prices in publicly listed radio companies began to escalate. The application of electricity also had an energising effect on people. Not only did it allow the automation of production lines, increasing quality and reducing prices, but also it began to deliver a whole range of appliances that ran on electricity.

Consumerism became rampant, which in itself is often a signal of an out-of-control economy or market. In addition, the stock market, traditionally the preserve of money experts and the seriously wealthy, became a craze. Everyone began to invest and, even more dangerously, began to believe they could get rich quickly and easily from a few well-placed bids.

To add fuel to the fire, credit became more and more easy to achieve, thanks to loose monetary policy and the development of new credit-related products and services. Trading on margin, where only a fraction of a share transaction’s worth had to be committed as a deposit, became extremely popular. Security for the loan was usually no more than the shares themselves.

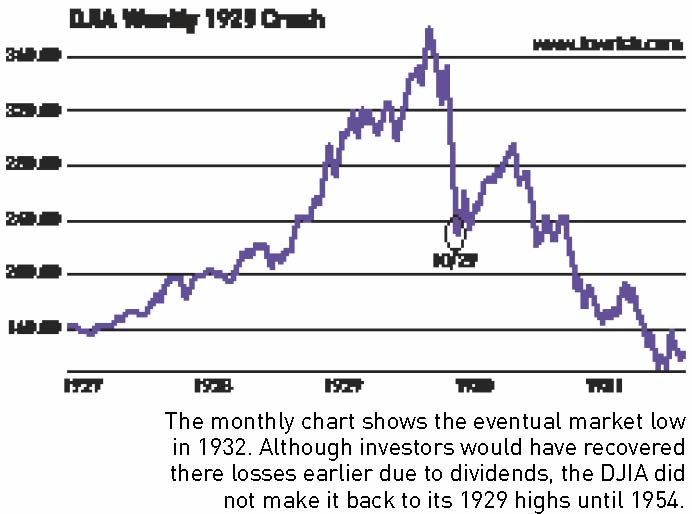

The economic good times really began to roll after the First World War but investment mania really started to get a grip in the late 1920s. Between 1926 and late 1929, the value of all US shares more than tripled from an estimated US$27b toUS$87b. By September 3, 1929, a key measure of the market, the Dow Jones Industrial Average Index, went from 100 to 381 in less than four years.

In mid-1928 the US Federal Reserve, which had maintained a loose monetary policy, began to push up interest rates, from 3.5% to 6% over 18 months, in a bid to dampen down over exuberance in the economy. This move was encouraged by President Herbert Hoover, who took office in March 1929, who had long been concerned at what he saw as excessive levels of speculation.

By late 1929 the effects were being felt. Fewer people had surplus money and corporate profits began to fall. Share prices soon followed. The beginning of the end came on October 24,1929, when the market fell by 9%. On that day, 12.9m shares were traded, a record and several times the normal volume.

By late 1929 the effects were being felt. Fewer people had surplus money and corporate profits began to fall. Share prices soon followed. The beginning of the end came on October 24,1929, when the market fell by 9%. On that day, 12.9m shares were traded, a record and several times the normal volume.

The ticker tape machine, which printed out trading information sent to it by telegraph, was operating up to an hour and a half behind the market, making it impossible for investors to find out what was happening. They imagined the worst and this was not assisted by brokers who stopped answering their phones.

By late morning, crowds of investors had gathered outside the New York Stock Exchange. Police were called in to prevent a riot. As one journalist of the day wrote: “It was as though the bear had become a living, visible thing. Some stood with feet apart and shoulders hunched forward as though to brace themselves against the gusts of selling orders which drove them about the floor like autumn leaves in a gale.”

By lunchtime on September 24th , the “Big Six “investment bankers of Wall Street, led by Morgan Stanley himself, were in a crisis meeting. The bankers reacted by putting on their bravest faces, and invested millions of dollars in purchasing shares. The gamble appeared to work and the market steadied.

President Hoover assisted them by making a public statement stressing the strength of the economy. By the afternoon of the 24th, the panic seemed over. Many major shares recovered most of their losses of the morning and stability returned on the Friday and Saturday morning of trading.

After a weekend of reflection, some investors had decided to quit at any costs while others believed it was a time to go bargain hunting. On Monday, October 28, an impressive 9.2 million shares exchanged hands. Almost all share prices went down that day and, unlike the previous Thursday, there was no recovery by the close of trading.

Also that day, the controver sial Smoot-Hawley bill implementing harsh tariffs on agricultural goods was enacted. The impact on America’s trading partners was enormous. Whether by coincidence or not, the next day - September 26, 1929 - saw the market collapse; a day that has gone down in history as “BlackTuesday”. On that day alone, 16.4 million shares were traded, volume that would not be repeated for another 39 years. The market fell 17.3%.That was when many investors found that margin trading was a double-edged sword. Using someone else’s money to buy shares made sense when the market was rising dramatically. However, when the market fell, investors found themselves liable for huge debts and were getting calls from their brokers to cover some of that loss. This time, it was the investors who stopped answering their phones.

sial Smoot-Hawley bill implementing harsh tariffs on agricultural goods was enacted. The impact on America’s trading partners was enormous. Whether by coincidence or not, the next day - September 26, 1929 - saw the market collapse; a day that has gone down in history as “BlackTuesday”. On that day alone, 16.4 million shares were traded, volume that would not be repeated for another 39 years. The market fell 17.3%.That was when many investors found that margin trading was a double-edged sword. Using someone else’s money to buy shares made sense when the market was rising dramatically. However, when the market fell, investors found themselves liable for huge debts and were getting calls from their brokers to cover some of that loss. This time, it was the investors who stopped answering their phones.

By November, the market had fallen by nearly two thirds to 145 but, driven by a growing recession, the selling didn’t stop and the market eventually bottomed in June 1932 at 34, a remarkable 91% below its peak.

Individuals lost their life savings, businesses and banks failed and the rest slashed spending or lending. Import volumes fell by two thirds in three years. The resulting impoverishment of other countries then caused exports to slump and national output halved.

Things were made worse by central banks that refused to loosen money supply, forcing businesses to close and forcing millions of people out of jobs. The depression lasted for a decade, basically until US began rearming for World War II.

Not everyone lost his or her fortune, however. Joseph Kennedy, father of the presidential family said to be one of the most ruthless and effective stock price manipulators of all time (a practice that was legal at the time), sold all his shares shortly before the crash. The story goes that he was having his shoes shined and the shoeshine boy offered him a hot tip. He immediately sold all his stocks, reasoning that even if shoeshine boys were in the market, there was no one left to buy stocks.

There have been many market crashes since the 1929 one, but none have been so drastic, so long lasting, and caused so much human misery. The old cliché of investors leaping out of buildings was actually for real.

- Last updated on .