What We Can Learn From Investment Manias Part 2

This is the second instalment of David McEwen’s series on the causes of bad investment behaviour, as depicted in classic investment bubbles through the ages. In the first part we considered how a tulip in 1637 came to be worth $1 million. This time around we look at some other famous bubbles.

Previous article What We Can Learn From Investment Manias Part 1.

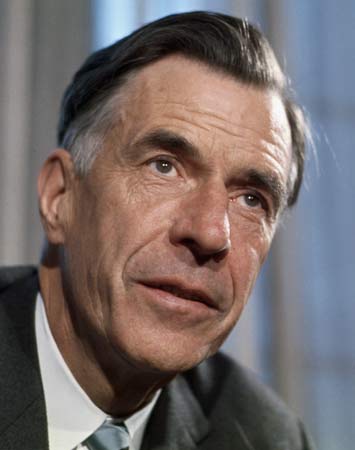

The illustrious economist John K Galbraith identified a clear pattern that every investment mania goes through. “The more obvious features of the speculative episode are manifestly clear to anyone open to understanding,” he wrote.

The illustrious economist John K Galbraith identified a clear pattern that every investment mania goes through. “The more obvious features of the speculative episode are manifestly clear to anyone open to understanding,” he wrote.

“Some artefact or some development, seemingly new and desirable…captures the financial mind or perhaps, more accurately, what so passes. Securities, land, objets d’art, and other property, when bought today, are worth more tomorrow. This increase and the prospect attract new buyers; the new buyers assure a further increase. Yet more are attracted; yet more buy; the increase continues. The speculation building on itself provides its own momentum.”

This frenzied race to easy riches can be seen in all the examples that follow. Also evident is the role of banks in virtually every great market boom and crash in history. Every crash is preceded by a boom that is fuelled by easy credit as banks pump money into the economy in their own pursuit of size, scale and market share.

The Mississippi Bubble, 1721

Easy credit has often been the downfall of the imprudent businessperson and the creation of a monetary bubble by a Scottish venturer John Law is still rated as one of the most spectacular booms and busts ever.

Law was born in Edinburgh in 1671 to a wealthy jewellery and money lending family. A good-looking rogue, he was famous for his vanity, success with the ladies and a passion for gambling.

After killing someone in a duel, Law was sent to prison for murder but escaped and left for Europe. A good head for numbers meant he had always been a very successful gambler and he quickly wormed his way into big-stakes games with the aristocracy.

After moving to Paris in 1715 he renewed a friendship with the Duke of Orleans, regent to the young King Louis XV. The regent’s job was to govern France until the heir to the throne, five-year-old Louis XV, was old enough to rule.

After moving to Paris in 1715 he renewed a friendship with the Duke of Orleans, regent to the young King Louis XV. The regent’s job was to govern France until the heir to the throne, five-year-old Louis XV, was old enough to rule.

Decades of war had virtually bankrupted the country, which was struggling under high taxes and debt defaults. Law thought he had a solution to France’s problems. He had been working on a theory for several years that a limit on money supply (which in those days constituted gold or silver coins) also put a brake on economic growth.

He believed that an issue of bank notes, supposedly backed by precious metals, would stimulate the economy. Inflation would be beaten by increased economic activity, which would soak up the extra notes in circulation, he theorised.

Having persuaded the Duke of the merits of his scheme, he established a bank, Banque Generale, in 1716. This quickly began to issue its own bank notes.

Thanks to Law’s connections at the palace, the bank was able to raise equity by purchasing government debt and using that as security for further loans. This was identical to the model established by the South Sea Company a few years earlier.

In late 1717 John Law took control of a failed business called the Mississippi Company that had rights to exploit land in the US. France’s territories in the US were relatively new but covered a wide area, stretching for 3,000 miles along the Mississippi River.

The company had monopoly rights to trade with parts of the newly colonised America, particularly the French-settled area of Louisiana – thought to be rich in minerals –and Canada, where beaver skins were a major commodity.

The Duke of Orleans, keen to find a way out of France’s financial crisis, took ownership in December 1718 of the Banque Generale, which was re-named Banque Royale. However, John Law continued to run the business.

Within a few months the Mississippi company, which had been renamed Compagnie d’Occident, gained another name, Compagnie des Indes, to reflect the expansion of its power to control all French trade in the world outside Europe.

Despite the name changes, the company continued to be known by its original title, Mississippi. It wasn’t long before the company’s influence extended to printing France’s currency and collecting its taxes. And so the groundwork was set for one of the biggest scams in history.

Such apparent guarantees of income and creditworthiness saw demand for company shares rocket. In a little over six months in late 1719 and early 1720, the company’s shares grew by 1900% from 500 livres per share to around 10,000.

The ability to generate apparently easy money attracted the less wealthy and a buoyant market in the shares was established. Some people made so much money in such a short term – millions of livre – that a new term was invented for them. That term is still with us today as millionaire.

The investment mania also generated another word still commonly used today, “speculation”, meaning to buy specie – the term at the time for company stock. To cement the financial arrangements, it was decreed in mid 1719 that each certificate of Mississippi stock would come with a bank note issued by the Banque Royal. These proved so popular that hundreds of millions of each were produced.

In January 1720, Law was appointed the Controller General and Superintendent General of Finance. That meant he had control of France’s finances as well as the company that was responsible for all of France’s foreign trade.

In January 1720, Law was appointed the Controller General and Superintendent General of Finance. That meant he had control of France’s finances as well as the company that was responsible for all of France’s foreign trade.

To stimulate demand for the newfangled paper money – an entirely new concept for most French people – Law announced that Banque Royale-issuednotes were legal tender for payments of more than 100 livres and that it was illegal to hold more than 500 livres in coins.

This was partly a reaction to increased demand by investors to redeem notes for coins. Such redemptions may have been a reaction to the increasing volumes of paper being issued. Some estimates put the increased value of currency in circulation during 1720 alone at around 200%.

Needless to say, extra money in circulation without a matching increase in goods and services soon resulted in higher prices. Inflation hit an annualised high in January 1720 of 276%. Law’s theory that economic growth would exceed or at least match growth in the money supply had proven incorrect.

By May 1720 Law and colleagues decided that company shares, set at 9,000 livres each, were too high and they announced that the face value would be reduced by 50%. After a public outcry the adjustment was cancelled, but public confidence in the shares had been damaged.

At the same time, the Duke began selling his Mississippi shares and his Banque Royale stopped redeeming notes for gold, destroying any confidence in their value. Desperately, Law announced that Banque Royale notes would be cancelled and replaced by new ones, secured by the revenues of the city of Paris.

Frantic scenes ensued as people swapped old bank notes for new and then converted those into coin. There weren’t enough currency reserves to back the notes and Law’s enemies took the opportunity to oust him from the company.

He left in disgrace and, by late the 1721, the shares of his company had slumped to a few hundred livres. Individual losses were massive and so many people were unable to repay loans that many banks failed. The suicide rate was reported to have doubled in a week. Bankers closed shop and left the cities where they had once been prominent citizens. The final outcome of Law’s grand economic experiment was that France’s economy ended up virtually ruined, a far worst state than it had been in just a few years earlier.

The Great Railroad Bubble, 1857

The invention of the steam train in early 19th Century Britain was a revolutionary technology with far-reaching implications. One country on which it had a particularly significant impact was the rapidly developing USA.

Trains were seen as an efficient way of opening up vast new tracts of land and expansion was rapid. In 1830, America had 23 miles of finished railroad track. Just ten years later there was 3,500 miles of railroad. That had nearly tripled to 9,000 by 1850 more than tripled again to 30,600 in 1860.

Trains were seen as an efficient way of opening up vast new tracts of land and expansion was rapid. In 1830, America had 23 miles of finished railroad track. Just ten years later there was 3,500 miles of railroad. That had nearly tripled to 9,000 by 1850 more than tripled again to 30,600 in 1860.

Railroad companies sprang up everywhere and raised funds through stock and bond issues to finance rapid growth. Investors, both local and international, especially British, believed the new technology would revolutionise business and deliver huge wealth in short order. This seemed to be the case when railroads helped thousands of people reach distant gold fields.

Stimulated by increases in the money supply, stock prices began to escalate. Titans of industry like Cornelius Vanderbilt and John Jacob Astor were busy raising massive amounts of capital for railroad construction, aided by a rash of new banks opening up and providing easy capital.

Construction was also encouraged by successive governments as a way of developing the country. By 1857 a buoyant market had turned into fully-fledged bubble, with the inevitable result. Several factors came together to cause a crash.

Lower European demand for grain coincided with bumper crops that drove down prices. Many farmers were unable to service bank debts. Also, huge imports to the US meant the country was a net exporter of gold. This created a domestic shortage, dangerous in a time when currency was backed by gold.

During the summer of 1857, banks raised interest rates in a bid to attract gold deposits to their nearly empty vaults. Higher interest rates put pressure on many railroads and those many speculators who had borrowed to invest in railroad securities.

The first indicator of trouble was the collapse of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company in August 1857. The firm had lent US$5m to railroad construction, which was slow in being repaid and lost millions more to a fraudulent manager.

Other banks became nervous and began to demand immediate payment of loans. They also became reluctant to make new loans. Nervous savers began to withdraw money from the banks and gold reserves plunged. A plan to replenish reserves with gold from the Californian fields failed when a ship carrying US$1.6m in gold and 400 passengers was sunk during a storm.

With a widespread shortage of gold, many banks were forced to stop making gold payments. Panic soon set in. Stock prices collapsed and many thousands of businesses closed their doors. A lack of credit brought construction of buildings and railroads to a halt and trade volumes shrank. By December 1857, businesses had lost a combined total of hundreds of millions of dollars and the nation entered a sharp recession that lasted until after the US Civil War.

Next : The US Stock Bubble, 1929 What We Can Learn From Investment Manias Part 3

- Last updated on .