Why does residential property seem to defy all the normal investment principles?

We found the following article on residential property markets prices thought provoking and thought we'd share it. Reproduced with the permission of the author, Tim Farrelly from his Proactive Asset Allocation Handbook - NZ Edition - June 2011.

We found the following article on residential property markets prices thought provoking and thought we'd share it. Reproduced with the permission of the author, Tim Farrelly from his Proactive Asset Allocation Handbook - NZ Edition - June 2011.

Why does residential property seem to defy all the normal investment principles?

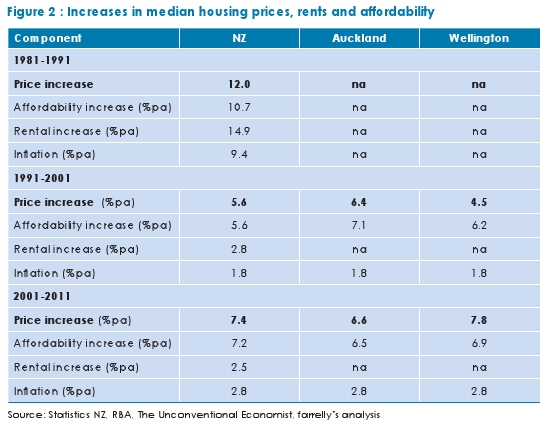

farrelly’s and others have long remarked upon the seeming ability of the residential housing market to defy normal investment principles. Under the Occam’s Razor view of the world, the key determinants of returns are growth in income and Price Earnings (PE) ratios. But both seem to have little to no relevance when attempting to forecast returns on residential property. For property, the PE ratio is the property value divided by net rents – and on that measure, prices have hovered in the range of 20 to 35 times earnings for years. What’s more, growth of rents over time often seems to bear little or no semblance to growth in prices as shown in Figure 2.

This issue of the Handbook looks at the residential property market in detail and proposes a framework for what drives prices. We test to see how that framework works in practice and then use it as a basis for forecasting returns over the next decade, and assessing the risks to those forecasts.

The residential property market is not a normal market

So why does the residential property market seem to defy all normal investment principals? Put simply, it is not a normal market!

In a normal market, investors buy assets that are most likely to give high returns and sell assets that are expected to give low returns. If something appears likely to rise in price, they want to own it; if it looks like it might fall in price, they stampede to the exits.

In contrast, the residential property market is dominated by homeowners, people who primarily want shelter which, along with food, is a basic human need. Do supermarket shoppers stampede for the exits if they believe that prices are too high? Hardly. They simply adjust their shopping list and keep buying - what they buy may change, but buy they do. The majority of home owners are just the same.

Think about a pair of home buyers after their first day of house hunting. Invariably, they return home deflated. Talk is along the lines of “Is our dream home really that far out of our range? I can’t believe how little we get for our money.” And, after that first day, the strategy becomes clear – they work out the maximum they can possibly spend and then go looking for the least worst place they can buy for that amount. What do they spend? Whatever the bank will lend them.

Compare that to a canny sharemarket investor who has spent some time studying the market and concluded that everything seems very expensive. Is it likely this investor would head down to the local bank manager to beg for the biggest loan that the manager is willing to advance, in order that the investor can maximise his/her exposure to the sharemarket? It would be crazy.

But that is what happens every day, over and over again, in the residential property market.

So why do house prices seem high?

farrelly’s believes it is because the demand for housing is greater than the supply. And in such an environment – and when simply staying out of the market is not an option for most – the only thing that limits the price paid is the supply of money, being the amount of money banks are willing to lend. To work that out, the banks look at how much income buyers earn and where current mortgage interest rates are, then use that information to calculate how much debt a potential borrower can safely service. So, when potential buyers’ earnings rise or interest rates fall, they can borrow more; similarly, if interest rates rise, the banks reduce the amount they are willing to lend.

Home buyers don’t automatically pay more for a given property just because they have had a pay rise. However, in the medium-term, the impact of thousands of buyers, all making similar assessments, will gradually move house prices up when average weekly earnings rise, or if interest rates fall. Similarly, prices should fall, after a suitable lag, when interest rates rise.

Key drivers of housing prices

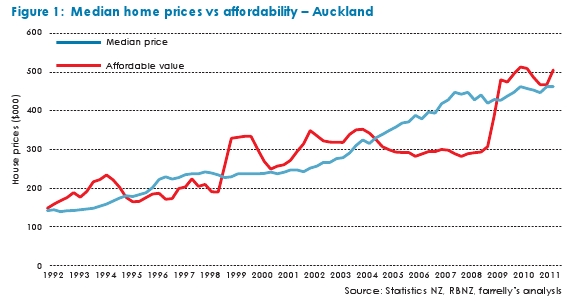

If this view of the market is correct, over the medium term, prices should move up and down at about the same rate as property affordability. Affordability is proportional to average weekly earnings divided by home loan interest rates. As earnings grow, households can afford to service larger loans and so property becomes more affordable. Similarly, lower interest rates also make property more affordable. Figure 1 shows how Auckland property prices have varied over time compared to affordability. Other cities, both in NZ and overseas, show similar patterns.

The first thing to note is that affordability is much more volatile than actual house prices. This is because changes in interest rates have a big affect on affordability – an interest rate decrease from 8% to 6% makes housing 25% more affordable. This doesn’t transmit immediately into the market; bankers take a while to change their lending ratios to take into account the new market conditions and buyers take a while to realise they can borrow more after lending ratios change. But eventually, after a year or two, affordability does seem to drive the market. Figure 2 illustrates how, over longer time frames, prices have moved much more in line with affordability than they have with growth in rents or inflation.

Secondly, Figure 1 shows that during 2004 to 2007, prices continued to rise even though affordability was slowly falling. During that period, interest rates crept up, pushing affordability down and creating a large gap between actual and affordable prices. While farrelly’s doesn’t have a strong opinion on why that gap grew to be so large, we did expect that at some time it would close up. As it turns out, the gap has closed mainly due to large interest rates falls which have made prices more affordable.

However, a note of caution! We believe New Zealand interest rates will move back to more normal, higher levels in due course and that move will result in affordability moving sharply downward again. It’s no time to be complacent. In the Forecasts in Focus section (page 10) returns are forecast for Auckland and Wellington residential property. Post the earthquakes in Christchurch, there are just far too many uncertainties to make any estimate of future residential property returns in that city. We just hope that the people of Christchurch are able to get life back to something resembling normality as soon as possible and in the meantime, send our best wishes to them as they cope with a myriad of day-to-day difficulties.

The data in Figure 2 and similar data from the Australian market reinforces our belief that, in the long term, affordability gives a good guide to price behaviour both conceptually and in practice.

The affordability model requires demand to exceed supply

This framework is predicated on the idea that there is a shortage in the supply of housing and that home owners will pay whatever they have to so long as the shortage of housing remains. This in turn relies on continued population growth in the major cities, as well as councils continuing to limit the density of dwellings and the release of land for development. Without insufficient supply, this model falls down and prices would begin a long slow slide back to more conventional valuation levels. This is what happened when the Japanese population stopped growing in the early 1990’s – Japanese residential property prices began a slow but steady fall that has them nearly some 60% lower than their peak 20 years ago. A frightening possibility, but an unlikely one,...

Source: farrelly's Proactive Asset Allocation Handbook - NZ Edition - June 2011.

- Last updated on .