Europe On The Brink

Europe on the Brink

The following article was written by Christian Hawkesby, Head of Fixed Income at Harbour Asset Management, drawing on his understanding of Europe from his experience at the Bank of England. An adridged version was published in the National Business Review on 7 October 2011.

New Zealand Fixed Income Monthly Commentary

6 October 2011 |

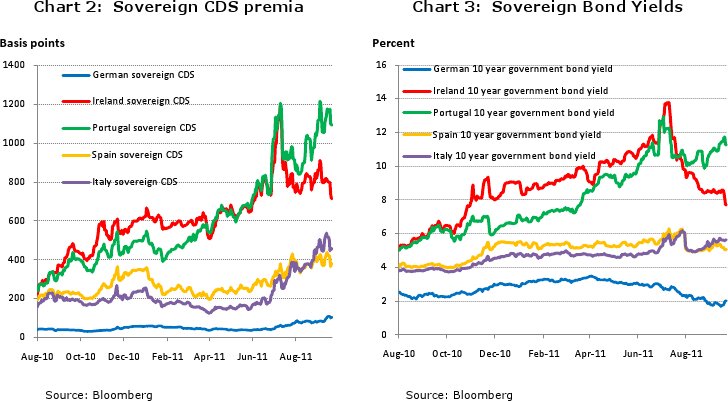

- The European sovereign crisis has worsened significantly in recent months. While European leaders are waiting for the July rescue package to receive parliamentary approvals, it already looks too little, too late.

- The crisis is now too large for the Europeans to deal with alone: they lack the clear leadership and financial resources to put a rescue beyond doubt. But policymakers are beginning to acknowledge the enormity of the problem.

- It is now in the best interests of countries outside of Europe to see the crisis resolved. The IMF is well placed to coordinate a global solution. This needs to include a Greek restructuring, support to periphery Europe, bank recapitalisations, support to funding markets, and structural reforms.

- In the meantime, in fixed income markets there is ample scope for bouts of optimism and disappointment, leading to more market volatility over coming months.

Herding Cats

During my time at the Bank of England, I experienced a small window into the way that Europe works (or doesn't work).

As the Bank's representative on one of the European Central Bank (ECB)'s working groups, I travelled to Frankfurt once a month to join representatives from 25 other countries: covering euro-ins (e.g. Germany, France, Italy), EU-ins-euro-outs (e.g. UK, Sweden), and euro-accession countries (e.g. Malta, Slovenia). In many cases each country was represented by a central bank and financial regulator. (In other committees you'd add someone from the finance ministry to a make up to 75 representatives.) There were a rainbow of cultures, attitudes and personalities; far too many to agree to an agenda or action points. Indeed, delegates from the same country often struggled to agree on a common line to take. The one thing we all had in common was that we had been sent with strict instructions not to commit unconditional support to any proposal. The ECB secretariat based in Frankfurt was ambitious and enthusiastic, but outnumbered. Furthermore, there were at least two other European-wide committees chaired by other European-wide official institutions with overlapping membership and agendas, but with equal ineffectiveness.

European decision making structures that we are watching in action now were designed with the memory of autocratic rule in the first half the 20th century fresh in the mind. The new post war Europe was modeled on consensual decision making with a multitude of checks and balances. It was purpose-designed to be slow and frustrating.

It's Time to Break up or Get Married

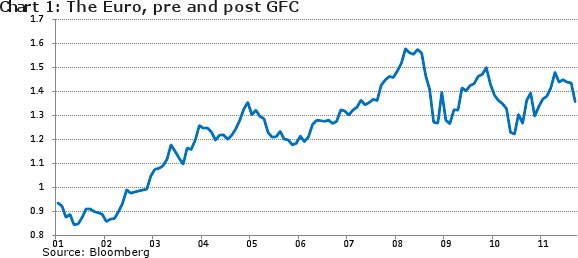

I finished my time on the working group in September 2004 with fond memories of the people and the one offsite meeting held in Malta. Those were the glory days for Europe and the euro. Economic growth was strong and markets were buoyant. Other countries were lining up for the privilege to join.

That was all before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) first broke in August 2007. The crisis facing Europe now is just another act in the same drama that started over four years ago. The crisis that started in structured product markets moved to threaten funding markets, then banking systems, the macroeconomy, small European sovereigns and now risks bringing down Europe itself. Each rescue attempt has created breathing space until the next, as the crisis has moved along to consume larger and larger victims. The stakes for Europe are now very high. At one level they are left with a choice to i) break up and go their separate ways or ii) bind each other closer together.

i. Euro break up

A lot of commentators talk about Greece leaving the euro as a potential solution to the crisis facing Greece and Europe. In the medium-term it would certainly help the Greek economy by enabling them to devalue their currency and gain the competitiveness to avoid years of recession.

It is possible for them to leave the euro: Greek notes (serial numbers) and coins (pictures) are physically distinguishable, and the Greek banking system has a separate payment system through the Greek central bank. But it would be an administrative and operational nightmare

that would cause enormous short-term disruption. Ironically, it was this sense of being irrevocable that was one of the major attractions of joining the euro, and a key advantage over the former regime of fixed exchange rates.

More importantly, it would immediately raise questions about what other weak peripheral countries would be next to leave, and would be seen as the first domino towards the end of the modern European experiment. Ireland and Portugal would be the first candidates to go, and Spain and Italy could go as well.

It was always clear to economists that the countries of the euro-area didn't meet criteria of an optimal currency area (and in the UK, the Chancellor Gordon Brown set these out as strict rules to guarantee than the UK didn't join).

The formulation of the euro currency was always seen as more of a political project than an economic project. That is way why Angela Merkel's efforts to contain that European crisis having not been couched in terms of saving Greece, but saving the euro. A break up of the euro would be a huge setback to all the steps taken to bind Europe together since WW2.

ii. Euro fiscal union

If the European politicians cannot stomach presiding over the end of the euro, the only other way to decisively stem the crisis is to bind each other closer together: to move from a trial relationship to a formal, binding marriage.

This means creating a full European fiscal union, in the same way that the United States runs a federal budget, gathers taxes and redistributes wealth federally, and borrows federally through the US Treasury Department. This would be a step in the right direction to meet the criteria for a common currency union, enabling resources to move more freely within the area. And it would mean that there would be no weak members on the fringes of Europe left to fend for themselves in financial markets. Europe would stand together, stabilised by its collective strength.

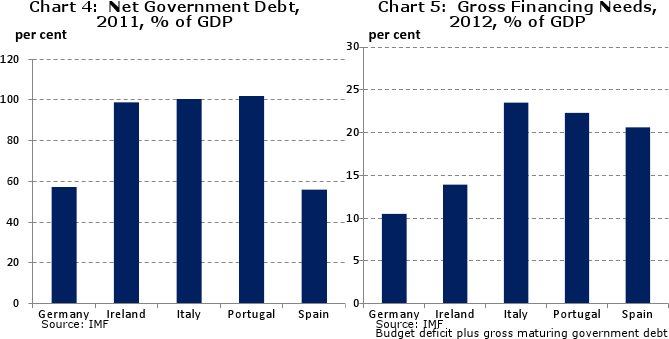

But this solution is politically unpalatable to the stronger countries in Europe, especially in Germany and the Netherlands where voters have no interest in paying for free-riders in the south. Furthermore, they don't want to create moral hazard, rescuing fiscally imprudent countries on easy terms and sending a message to others they don't have to tighten their belts. But dealing with moral hazard at the height of a crisis is a very dangerous strategy, and can lead to an even more causalities and a bigger mess to tidy up afterwards.

Lessons from the UK and US Banking Crises

So if a euro break-up or European fiscal union is out of the question, what other options do policy makers in Europe have to steam the crisis?

In September/October 2008, financial markets in London and New York had the same sense of standing on the edge of an abyss as faced now in Frankfurt and Brussels. Back then, the Anglo-Saxon financial system was on the edge of collapse. Looking at the response of the UK and US authorities in that situation suggests that the Europeans need to tackle this crisis on at least six fronts.

- A restructuring of Greek government debt that lowers the prices to a level where investors see value.

- Support of other European periphery countries through large scale purchases of their government debt in secondary markets, to signal to markets that authorities believe these have become undervalued.

- A recapitalisation of European banks, to strengthen their balance sheets after the haircuts imposed by the Greek restructuring, and to a level that gives markets absolute confidence about their strength.

- Support for bank funding markets, through the ECB re-opening all the special funding and liquidity mechanisms that were created at the height of the GFC in 2009, to ensure that banks have confidence that funding markets remain open.

- Support to the macroeconomy, through loosening monetary policy, with the ECB reversing recent interest rate hikes to bring official rates back to near zero.

- A plan for structural reforms, to address the structural vulnerabilities within Europe that led up to the crisis, including lack of fiscal discipline.

Nearing a Grand Plan

The media have reported that the mood the G20 and IMF meetings at the end of September was particular gloomy and increasingly desperate.

Following these official sector meetings, there has been growing talk of a grand package that would include some combination of 1 to 3 above – a Greek restructuring, support to periphery countries, and bank recapitalization. The centerpiece of the plan would be to bolster the size of a new rescue package by leveraging the size of the last European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) rescue package proposed back in 21 July. In effect, that $400 billion package would be used as equity in a leveraged vehicle with an overall capacity closer to $2 trillion. The details are a long way from being worked through.

But there are huge risks involved in working this idea into a concrete plan that gets agreed and implemented.

Setting aside the complexities of working up the plan, the most fundamental hurdle is that the existing 21 July EFSF package is still in the process of getting parliamentary approval by European member countries. Reaching agreement in all countries is not without risk. Revising the package again may restart the process of both parliamentary and constitutional approvals. As the rescue package grows, the remaining AAA-rated countries in Europe are likely to become increasingly fearful that it will result in them being downgraded too. Public opinion in northern European countries is moving against the euro. And all the while Greece inches towards the day it runs out of cash, with civil disorder mounting in the face of more austerity measures and no hope of economic recovery.

At the very least, to stem the crisis, the European authorities need to speak with a single voice and ensure that Greece receives its next installment to remove speculation about its immediate future. But even that may not be enough.

Time for Some Global Leadership

It has got to the stage where the European sovereign crisis has grown too large for the Europeans to deal with alone: they lack the required clear leadership; and just as importantly they lack sufficient financial resources to put a rescue beyond doubt.

The IMF is uniquely placed to provide that leadership and marshal the resources for a comprehensive response. The IMF was created after WW2, for this very purpose of "provid(ing) the machinery for consultation and collaboration on international monetary problems". While the majority of IMF rescues in the past 30 years have been to deal with EME exchange rate crises, it is easy to forget that as recently as 1976 the UK received large-scale IMF support. The IMF is the best organisation available to show the clear leadership that has been lacking in Europe. The IMF itself was without a leader after the departure of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, but can now take things forward under Christine Lagarde.

The European crisis has also grown to the size that it is in the best interests of countries outside of Europe to see it resolved, and to reduce the spillover impact on other financial systems and the broader global economy. Officials in the US are clearly worried and calling for urgent action. China has vast financial resources and has already made very public attempts to calm European markets by directly buying European government bonds. And Japanese officials have recently said that they would consider joining a global package to support Europe.

The IMF is well positioned to marshal the resources of its members, the resources from the EFSF, and additional commitments from a coalition of the willing. While this would be no easy task, moving the crisis command centre to the IMF in Washington would acknowledge

the global nature of the problem and solution, and address the clear challenge of herding cats in Frankfurt and Brussels.

Implications for the NZ economy and fixed income

Back in July, the RBNZ gave a clear signal that it was ready to start raising the Official Cash Rate (OCR), to remove the 50 basis point insurance from March, subject to the global outlook not deteriorating significantly.

Since then, the US economy looks to have dropped into stall speed, the European sovereign crisis has worsened, commodity prices and emerging market equities have began to wobble, and the NZ Q2 GDP number disappointed at 0.1% for the quarter removing any urgency from the RBNZ to hike interest rates

The world looks a lot more fragile than back in July.

While we are hopeful that European policymakers will be resourceful and address their crisis, there appears to ample scope for bouts of optimism and disappointment, leading to more market volatility over coming months, and continued flight to safety into government bonds. Furthermore, while the strains in global credit markets have reached the Australian iTraxx Index, they have yet to materially impact the Australasian cash credit market. This all leads us to a position of expecting New Zealand interest rates to stay low for a while for longer, and continuing our programme of lightening exposures to subordinate and perpetual debt.

IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER

The New Zealand Fixed Income Commentary is given in good faith and has been prepared from published information and other sources believed to be reliable, accurate and complete at the time of preparation but its accuracy and completeness is not guaranteed. Information and any analysis, opinions or views contained herein reflect a judgement at the date of preparation and are subject to change without notice. The information and any analysis, opinions or views made or referred to is for general information purposes only. To the extent that any such contents constitute advice, they do not take into account any person's particular financial situation or goals, and accordingly, do not constitute personalised financial advice under the Financial Advisers Act 2008, nor do they constitute advice of a legal, tax, accounting or other nature to any person.. The bond market is volatile. The price, value and income derived from investments may fluctuate in that values can go down as well as up and investors may get back less than originally invested. Past performance is not indicative of future results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance. Bonds and bond funds carry interest rate risk (as interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa), inflation risk and issuer credit and default risks. Where an investment is denominated in a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may have an adverse effect on the value, price or income of the investment. Reference to taxation or the impact of taxation does not constitute tax advice. The rules on and bases of taxation can change. The value of any tax reliefs will depend on your circumstances. You should consult your tax adviser in order to understand the impact of investment decisions on your tax position. To the maximum extent permitted by law, no liability or responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage, direct or consequential, arising from or in connection with this document or its contents. Actual performance of investments managed by Harbour Asset Management Limited will be affected by management charges. No person guarantees the performance of funds managed by Harbour Asset Management Limited.

- Last updated on .